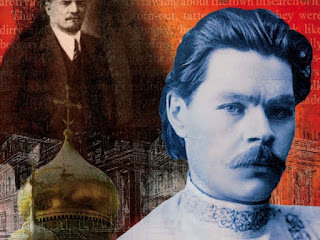

मक्सिम गोर्की की कहानी - वह लड़का Maxim Gorky's Story - The little boy

मक्सिम गोर्की की कहानी - वह लड़का

For English version please scroll down

यह छोटी-सी कहानी सुनाना काफी कठिन

होगा-इतनी सीधी-सादी है यह! जब मैं अभी छोटा ही था, तो गरमियों और वसन्त के दिनों में रविवार को, अपनी गली के बच्चों को इकट्ठा कर लेता था और उन्हें खेतों के पार,

जंगल में ले जाता था। इन पंछियों की तरह चहकते,

छोटे बच्चों के साथ दोस्तों की तरह रहना मुझे

अच्छा लगता था।

बच्चों को भी नगर की धूल और भीड़ भरी गलियों से

दूर जाना अच्छा लगता था। उनकी माँएँ उन्हें रोटियाँ दे देतीं, मैं कुछ मीठी गोलियाँ खरीद लेता, क्वास की एक बोतल भर लेता और फिर किसी गड़रिये की

तरह भेड़ों के बेपरवाह मेमनों के पीछे-पीछे चलता जाता-शहर के बीच, खेतों के पार, हरे-भरे जंगल की ओर, जिसे

वसन्त ने अपने सुन्दर वस्त्रों से सजा दिया होता।

आमतौर पर हम सुबह-सुबह ही शहर से बाहर निकल आते,

जब कि चर्च की घण्टियाँ बज रही होतीं और बच्चों

के कोमल पाँवों के जमीन पर पड़ने से धूल उठ रही होती। दोपहर के वक्त, जब दिन की गरमी अपने शिखर पर होती, तो खेलते-खेलते थककर, मेरे मित्र जंगल के एक कोने में इकट्ठे हो जाते। तब खाना खा लेने के

बाद छोटे बच्चे घास पर ही सो जाते-झाड़ियों की छाँव में-जबकि बड़े बच्चे मेरे

चारों ओर घिर आते और मुझे कोई कहानी सुनाने के लिए कहते। मैं कहानी सुनाने लगता और

उसी तेजी से बतियाता, जिससे मेरे दोस्त और जवानी के

काल्पनिक आत्मविश्वास तथा जिन्दगी के मामूली ज्ञान के हास्यास्पद गर्व के बावजूद

मैं अक्सर अपने आपको विद्वानों से घिरा हुआ किसी बीस वर्षीय बच्चे-सा महसूस करता।

हमारे ऊपर अनन्त आकाश फैला है, सामने है जंगल की विविधता-एक जबरदस्त खामोशी में

लिपटी हुई; हवा का कोई झोंका खड़खड़ाता हुआ पास

से निकल जाता है, कोई फुसफुसाहट तेजी से गुजर जाती है,

जंगल की सुवासित परछाइयाँ काँपती हैं और एक बार

फिर एक अनुपम खामोशी आत्मा में भर जाती है।

आकाश के नील विस्तार में श्वेत बादल धीरे-धीरे

तैर रहे हैं, सूरज की रोशनी से तपी धरती से देखने

पर आसमान बेहद शीतल दिखता है और पिघलते हुए बादलों को देखकर बड़ा अजीब-सा लगता है।

और मेरे चारों ओर हैं ये छोटे-छोटे, प्यारे बच्चे, जिन्हें जिन्दगी के सभी गम और खुशियाँ जानने के लिए मैं बुला लाया

हूँ।

वे थे मेरे अच्छे दिन-वे ही थीं असली दावतें,

और जिन्दगी के अँधेरों से ग्रसित मेरी आत्मा,

जो बच्चों के खयालों और अनुभूतियों की स्पष्ट

विद्वत्ता में नहाकर तरो-ताजा हो उठती थी।

एक दिन जब बच्चों की भीड़ के साथ शहर से निकलकर

मैं एक खेत में पहुँचा, तो हमें एक अजनबी मिला - एक छोटा-सा

यहूदी - नंगे पाँव, फटी कमीज, काली भृकुटियाँ, दुबला

शरीर और मेमने-से घुँघराले बाल। वह किसी वजह से दुखी था और लग रहा था कि वह अब तक

रोता रहा है। उसकी बेजान काली आँखें सूजी हुईं और लाल थीं, जो उसके भूख से नीले पड़े चेहरे पर काफी तीखी लग रही थीं। बच्चों की

भीड़ के बीच से होता हुआ, वह गली

के बीचोंबीच रुक गया, उसने अपने पाँवों को सुबह की ठण्डी

धूल में दृढ़ता से जमा दिया और सुघड़ चेहरे पर उसके काले ओठ भय से खुल गये - अगले

क्षण, एक ही छलाँग में, वह फुटपाथ पर खड़ा था।

“उसे पकड़ लो!” सभी बच्चे एक साथ खुशी से चिल्ला

उठे, “नन्हा यहूदी! नन्हे यहूदी को पकड़

लो!”

मुझे उम्मीद थी कि वह भाग खड़ा होगा। उसके दुबले,

बड़ी आँखोंवाले चेहरे पर भय की मुद्रा अंकित थी।

उसके ओठ काँप रहे थे। वह हँसी उड़ाने वालों की भीड़ के शोर के बीच खड़ा था। वह

पाँव उठा-उठाकर अपने आपको जैसे ऊँचा बनाने को कोशिश कर रहा था। उसने अपने कन्धे

राह की बाड़ पर टिका दिये थे और हाथों को पीठ के पीछे बाँध लिया था।

और तब अचानक वह बड़ी शान्त और साफ और तीखी आवाज

में बोल उठा - “मैं तुम लोगों को एक खेल दिखाऊँ?”

पहले तो मैंने सोचा कि यह उसका आत्मरक्षा का कोई

तरीका रहा होगा - बच्चे उसकी बात में रुचि लेने लगे और उससे दूर हट गये। केवल बड़ी

उम्र के और अधिक जंगली किस्म के लड़के ही उसकी ओर शंका और अविश्वास से देखते रहे -

हमारी गली के लड़के दूसरी गलियों के लड़कों से झगड़े हुए थे। उनका पक्का विश्वास

था कि वे दूसरों से कहीं ज्यादा अच्छे हैं और वे दूसरों की योग्यता की ओर ध्यान

देने को भी तैयार नहीं थे।

पर छोटे बच्चों के लिए यह मामला एकदम सीधा-सादा

था।

“दिखाओ - जरूर दिखाओ!”

वह खूबसूरत, दुबला-पतला लड़का बाड़ से परे हट गया। उसने अपने छोटे-से शरीर को पीछे

की ओर झुकाया। अपनी अँगुलियों से जमीन को छुआ और अपनी टाँगों को ऊपर की ओर उछालकर

हाथों के बल खड़ा हो गया।

तब वह घूमने लगा, जैसे कोई लपट उसे झुलसा रही हो - वह अपनी बाँहों और टाँगों से खेल

दिखाता रहा। उसकी कमीज और पैण्ट के छेदों में से उसके दुबले-पतले शरीर की भूरी खाल

दिखाई दे रही थी - कन्धे, घुटने

और कुहनियाँ तो बाहर निकले ही हुए थे। लगता था, अगर एक बार फिर झुका, तो ये

पतली हड्डियाँ चटककर टूट जाएँगी। उसका पसीना चूने लगा था। पीठ पर से उसकी कमीज

पूरी तरह भीग चुकी थी। हर खेल के बाद वह बच्चों की आँखों में, बनावटी, निर्जीव

मुसकराहट लिये हुए, झाँककर देख लेता। उसकी चमक रहित काली

आँखों का फैलना अच्छा नहीं लग रहा था - जैसे उनमें से पीड़ा झलक रही थी। वे अजीब

ही ढंग से फड़फड़ाती थीं और उसकी नजर में एक ऐसा तनाव था, जो बच्चों की नजर में नहीं होता। बच्चे चिल्ला-चिल्लाकर उसे उत्साहित

कर रहे थे। कई-एक तो उसकी नकल करने लगे थे।

लेकिन अचानक ये मनोरंजक क्षण खत्म हो गये। लड़का

अपनी कलाबाजी छोड़कर खड़ा हो गया और किसी अनुभवी कलाकार की-सी नजर से बच्चों की ओर

देखने लगा। अपना दुबला-सा हाथ आगे फैलाकर वह बोला, “अब मुझे कुछ दो!”

वे सब खामोश थे। किसी ने पूछा, “पैसे?”

“हाँ,” लड़के

ने कहा।

“यह अच्छी रही! पैसे के लिए ही करना था, तो हम भी ऐसा कर सकते थे...”

लड़के हँसते हुए और गालियाँ बकते हुए खेतों की ओर

दौड़ने लगे। दरअसल उनमें से किसी के पास पैसे थे भी नहीं और मेरे पास केवल सात

कोपेक थे। मैंने दो सिक्के उसकी धूल भरी हथेली पर रख दिये। लड़के ने उन्हें अपनी

अँगुली से छुआ और मुसकराते हुए बोला, “धन्यवाद!”

वह जाने को मुड़ा, तो मैंने देखा कि उसकी कमीज की पीठ पर काले-काले धब्बे पड़े हुए थे।

“रुको, वह

क्या है?”

वह रुका, मुड़ा,

उसने मेरी ओर ध्यान से देखा और बड़ी शान्त आवाज

में मुस्कराते हुए बोला, “वह,

पीठ पर? ईस्टर

के मौके पर एक मेले में ट्रपीज करते हुए हम गिर पड़े थे - पिता अभी तक चारपाई पर

पड़े हैं, पर मैं बिलकुल ठीक हूँ।”

मैंने कमीज उठाकर देखा - पीठ की खाल पर, बायें कन्धे से लेकर जाँघ तक, एक काला जख़्म का निशान फैला हुआ था, जिस पर मोटी, सख्त पपड़ी जम चुकी थी। अब खेल दिखाते समय पपड़ी फट गयी थी और वहाँ से

गहरा लाल खून निकल आया था।

“अब दर्द नहीं होता,” उसने मुस्कराते हुए कहा, “अब

दर्द नहीं होता... बस, खुजली होती है...”

और बड़ी बहादुरी से, जैसे कोई हीरो ही कर सकता है, उसने

मेरी आँखों में झाँका और किसी बुजुर्ग की-सी गम्भीर आवाज में बोला, “तुम क्या सोचते हो कि अभी मैं अपने लिए काम कर

रहा था! कसम से-नहीं! मेरे पिता... हमारे पास एक पैसा तक नहीं है। और मेरे पिता

बुरी तरह जख्मी हैं। इसलिए - एक को तो काम करना ही पड़ेगा, साथ ही... हम यहूदी हैं न! हर आदमी हम पर हँसता है... अच्छा अलविदा!”

वह मुस्कराते हुए, काफी खुश-खुश बात कर रहा था। और तब अपने घुँघराले बालोंवाले सिर को

झटका देकर अभिवादन करते हुए वह चला गया - उन खुले दरवाजों वाले घरों के पार,

जो अपनी काँच की मारक उदासीनता भरी आँखों से उसे

घूर रहे थे।

ये बातें कितनी साधारण और सीधी हैं - हैं न?

लेकिन अपने कठिनाई के दिनों में मैंने अक्सर उस

लड़के के साहस को याद किया है - बड़ी कृतज्ञता से भर कर!

It is hard to tell this little story,—it is so simple. When

I was a youth, I used to gather the children of our street on Sunday mornings

during the spring and summer seasons and take them with me to the fields and

woods. I took great pleasure in the friendship of these little people, who were

as gay as birds.

The children were only too glad to leave the dusty, narrow

streets of the city. Their mothers provided them with slices of bread, while I

bought them dainties and filled a big bottle with cider, and like a shepherd,

walked behind my carefree little lambs, while we passed through the town and

the fields on our way to the green forest, beautiful and caressing in its array

of Spring.

We always started on our journey early in the morning when

the church bells were ushering in the early mass, and we were accompanied by

the chimes and the clouds of dust raised by the children's nimble feet.

In the heat of noon, exhausted with playing, my companions

would gather at the edge of the forest, and after that, having eaten their

food, the smaller children would lie down and sleep in the shade of hazel and

snow-ball trees, while the ten-year-old boys would flock around me and ask me

to tell them stories. I would satisfy their desire, chattering as eagerly as

the children themselves, and often, in spite of the self-assurance of youth and

the ridiculous pride which it takes in the miserable crumbs of worldly wisdom

it possesses, I would feel like a twenty-year-old child in a conclave of sages.

Overhead is the blue veil of the spring sky, and before us

lies the deep forest, brooding in wise silence. Now and then the wind whispers

gently and stirs the fragrant shadows of the forest, and again does the

soothing silence caress us with a motherly caress. White clouds are sailing

slowly across the azure heavens. Viewed from the earth, heated by the sun, the

sky appears cold, and it is strange to see the clouds melt away in the blue.

And all around me—little people, dear little people, destined to partake of all

the sorrows and all the joys of life.

These were my happy days, my true holidays, and my soul

already dusty with the knowledge of life's evil was bathed and refreshed in the

clear-eyed wisdom of child-like thoughts and feelings.

Once, when I was coming out of the city on my way to the

fields, accompanied by a crowd of children we met an unknown little Jewish boy.

He was barefooted and his shirt was torn; his eyebrows were black, his body

slim and his hair grew in curls like that of a little sheep. He was excited and

he seemed to have been crying. The lids of his dull-black eyes, swollen and

red, contrasted with his face, which, emaciated by starvation, was ghastly

pale.

Having found himself face to face with the crowd of

children, he stood still in the middle of the road, burrowing his bare feet in

the dust, which early in the morning is so deliciously cool. In fear, he half

opened the dark lips of his fair mouth,—the next second he leaped right on to

the sidewalk.

"Catch him!" the children started to shout gaily

and in a chorus. "A Jewish boy! Catch the Jew boy!"

I waited, thinking that he would run away. His thin,

big-eyed face was all fear; his lips quivered; he stood there amid the shouts

and the mocking laughter. Pressing his shoulders against the fence and hiding

his hands behind his back, he stretched and strangely appeared to have grown

bigger.

But suddenly he spoke,—very calmly and in a distinct and

correct Russian.

"If you wish,—I will show you some tricks."

I took this offer for a means of self-defence. But the

children at once became interested. The larger and coarser boys alone looked

with distrust and suspicion on the little Jewish boy. The children of our

street were in a state of guerilla warfare with the children of other streets;

in addition, they were deeply convinced of their own superiority and were loath

to brook the rivalry of other children.

The smaller boys approached the matter more simply.

"Come on, show us," they shouted.

The handsome, slim boy moved away from the fence, bent his

thin body backward, and touching the ground with his hands, he tossed up his

feet and remained standing on his arms, shouting:

"Hop! Hop! Hop!"

Then he began to spin in the air, swinging his body lightly

and adroitly. Through the holes of his shirt and pants we caught glimpses of

the greyish skin of his slim body, of his sharply bulging and angular

shoulder-blades, knees and elbows. It seemed to us as if with one more twist of

his body his thin bones would crack and break into pieces.

He worked hard until the shirt grew wet with sweat about his

shoulders. After each especially daring feat he looked into the children's

faces with an artificial, weary smile, and it was unpleasant to see his dull

eyes, grown large with pain. Their strange and unsteady glance was not like

that of a child.

The lads encouraged him with loud outcries. Many imitated

him, rolling in the dust and shouting for joy, pain and envy. But the joyous

minutes were soon over when the boy, bringing his exhibition to an end, looked

upon the children with the benevolent smile of a thoroughbred artist and

stretching forth his hand said:

"Now give me something."

We all became silent, until one of the children said:

"Money?"

"Yes," said the lad.

"Look at him," said the children.

"For money, we could do those tricks ourselves."

The audience became hostile toward the artist, and betook

itself to the field, ridiculing and insulting him. Of course, none of them had

any money. I myself, had only seven kopecks about me. I put two coins in the

boy's dusty palm. He moved them with his finger and with a kindly smile said:

"Thank you."

He went away, and I noticed that his shirt around his back

was all in black blotches and was clinging close to his shoulder-blades.

"Hold on, what is it?"

He stopped, turned about, scrutinised me and said distinctly,

with the same kindly smile:

"You mean the blotches on my back? That's from falling

off the trapeze. It happened on Easter. My father is still lying in bed, but I

am quite well now."

I lifted his shirt. On his back, running down from his left

shoulder to the side, was a wide dark scratch which had now become dried up

into a thick crust. While he was exhibiting his tricks the wound broke open in

several spots and red blood was now trickling from the openings.

"It doesn't hurt any more," said he with a smile.

"It doesn't hurt, it only itches."

And bravely, as it becomes a hero, he looked in my eyes and

went on, speaking like a serious grown-up person:

"You think—I have been doing this for myself? Upon my

word—I have not. My father ... there is not a crust of bread in the house, and

my father is lying badly hurt. So you see, I have to work hard. And to make

matters worse, we are Jews, and everybody laughs at us. Good-bye."

He spoke with a smile, cheerfully and courageously. With a

nod of his curly head, he quickly went on, passing by the houses which looked

at him with their glass eyes, indifferent and dead.

All this is insignificant and simple, is it not?

Yet many a time in the darkest days of my life I remembered

with gratitude the courage and bravery of the little Jewish boy. And now, in

these sorrowful days of suffering and bloody outrages which fall upon the grey

head of the ancient nation, the creator of Gods and religion,—I think again of

the boy, for in him I see the symbol of true manly bravery,—not the pliant

patience of slaves, who live by uncertain hopes, but the courage of the strong

who are certain of their victory.

Comments

Post a Comment