कहानी - डाकचौकी का चौकीदार / अलेक्सान्द्र पूश्किन Story - The Stationmaster / Alexander Pushkin

कहानी - डाकचौकी का चौकीदार / अलेक्सान्द्र पूश्किन

(मूल रूसी भाषा से अनुवाद आ. चारुमति रामदास)

मुंशी सरकार का

तानाशाह डाकचौकी

का

- राजकुमार

व्याज़ेम्स्की

डाकचौकी के

चौकीदारों को किसने गालियाँ नहीं दी होंगी, किसका

उनसे झगड़ा न हुआ होगा? किसने क्रोध में आकर उनसे शिकायत

पुस्तिका न माँगी होगी, जिसमें वह अपनी व्यर्थ की शिकायत

दर्ज कर सकें: बदमिजाज़ी, बदतमीज़ी और बदसुलूकी के बारे में?

कौन उन्हें भूतपूर्व धूर्त मुंशी या फिर मूरोम के डाकू नहीं समझता,

जो मानवता के नाम पर बदनुमा दाग़ हैं? मगर,

फिर भी, आइए, उनके स्थान

पर स्वयम् को रखकर, उनके बारे में तटस्थता से विचार कर,

उनके साथ कुछ इन्साफ़ करें।

डाकचौकी का चौकीदार आख़िर क्या बला है? चौदहवीं श्रेणी का पीड़ित-शोषित जीव, ताड़न-उत्पीड़न से जिसकी रक्षा कभी-कभार यह सरकारी वर्गीकरण कर देता है, मगर हमेशा नहीं (अपने पाठकों के विवेक पर आधारित है मेरा यह कथन)। क्या ज़िम्मेदारी है इस प्राणी की जिसे राजकुमार व्याज़ेम्स्की व्यंग्य से ‘तानाशाह’ कहता है? यह कालेपानी की सज़ा तो नहीं? न दिन में चैन, न रात में। उबाऊ सफ़र से संचित पूरे क्रोध को मुसाफ़िर इस मुंशी-चौकीदार पर उँडेल देता है। चाहे मौसम ख़राब हो, या रास्ता ऊबड़-खाबड़, कोचवान ढीठ हो या फिर घोड़े ज़िद्दी हों– दोष है सिर्फ चौकीदार का। उसके जीर्ण-शीर्ण झोंपड़े में प्रवेश करते ही मुसाफ़िर उसे यूँ देखता है, जैसे किसी शत्रु को देख रहा हो। अगर इस बिन बुलाए मेहमान से शीघ्र छुटकारा मिल जाए तो सौभाग्य समझिए, और यदि घोड़े न हों तो? …या ख़ुदा! कैसी गालियाँ, कैसी धमकियाँ सुनने को मिलती हैं। बारिश और कीचड़ में उसे आँगन में भागना पड़ता है, तूफ़ान में, भीषण बर्फीले मौसम में उसे ड्योढ़ी पर जाना पड़ता है, ताकि क्रोधित मेहमान की चीखों और घूँसों से पल भर को राहत मिले।

जनरल आता है,

थरथर काँपता हुआ चौकीदार उसे अंतिम दो “त्रोयका”

दे देता है, और डाकगाड़ी भी। जनरल रवाना हो

जाता है, बिना धन्यवाद दिए। पाँच मिनट बाद घण्टी की आवाज़ और

घुड़सवार संदेशवाहक उसके सामने मेज़ पर अपना यात्रापत्र फेंकता है…

यह सब भली भांति

देखने पर हृदय उसके प्रति क्रोध के स्थान पर सहानुभूति से भर जाता है। कुछ और

शब्द: पिछले बीस वर्षों से मैं रूस के चप्पे-चप्पे का सफ़र कर चुका हूँ,

सभी राजमार्गों से परिचित हूँ। कोचवानों की कई पीढ़ियों को जानता

हूँ। डाकचौकी का शायद ही कोई चौकीदार होगा, जिसे मैं नहीं

जानता। शायद ही ऐसा कोई होगा, जिससे मेरा पाला नहीं पड़ा।

यात्राओं के दौरान हुए दिलचस्प अनुभवों को शीघ्र ही प्रकाशित करना चाहता हूँ। अभी

सिर्फ यही कहूँगा: डाकचौकी के चौकीदारों के वर्ग की समाज में एकदम गलत छबि बनाई गई

है। ये अभिशप्त चौकीदार वास्तव में बड़े शांतिप्रिय किस्म के होते हैं, स्वभाव से सेवाभावी, मिलनसार, नम्र,

धन का कोई लोभ नहीं। उनकी बातचीत से (जिसे मुसाफ़िर अनसुना कर देते

हैं) कई दिलचस्प और ज्ञानवर्धक बातें पता चलती हैं। जहाँ तक मेरा सवाल है, तो मैं स्वीकार करता हूँ, कि राजकीय कार्य से जा रहे

छठी श्रेणी के किसी कर्मचारी से बातें करने के स्थान पर मैं इन चौकीदारों की बातें

सुनना ज़्यादा पसन्द करता हूँ।

अनुमान लगाना

कठिन नहीं है कि चौकीदारों की जमात में मेरे परिचित हैं। सचमुच उनमें से एक की स्मृति

तो मेरे लिए बहुमूल्य है। परिस्थितिवश हम एक दूसरे के निकट आए थे और अब उसी के

बारे में मैं अपने प्रिय पाठकों को बताने जा रहा हूँ।

सन् 1816

के मई के महीने में मुझे प्रदेश के एक मार्ग पर जाने का मौका मिला

जो अब नष्ट हो चुका है। मैं एक छोटा अफ़सर था, किराए की गाड़ी

पर चलता था और दो घोड़ों का किराया दे सकता था। इस कारण चौकीदार मुझसे शिष्टता से

पेश नहीं आते, और अक्सर मुझे वह लड़कर ही मिलता था, जिसका, मेरे हिसाब से मैं हकदार था। जब मेरे लिए

तैयार की गई ‘त्रोयका’ वह ऐन वक्त पर

किसी बड़े अफ़सर को दे देता तो जवान और तुनकमिजाज़ होने के कारण मैं चौकीदार के

कमीनेपन एवम् तंगदिली पर खीझ उठता। इस बात से भी मैं कितने ही दिनों तक समझौता न

कर पाया कि गवर्नर को भोजन परोसते वक्त यह पक्षपाती, दुष्ट

सेवक मुझे कुछ भी परोसे बगैर बिल्कुल मेरे सामने से ही खाद्य-पदार्थ ले जाता। आज

ये सब बातें मुझे तर्कसंगत प्रतीत होती हैं। सचमुच, यदि ‘हैसियत का सम्मान करें’ के स्थान पर ‘बुद्धि का सम्मान करें’ कहावत लागू होती तो न जाने हम

लोगों का क्या हाल हुआ होता? कैसे-कैसे वाद-विवाद उठ खड़े

होते: तब सेवक किसे पहले भोजन परोसते? मगर, मेरी कहानी की ओर चलें।

गर्मी और

उमस-भरा दिन था। स्टेशन से तकरीबन तीन मील पहले बूँदाबाँदी शुरू हुई,

मगर एक ही मिनट में धुआँधार बारिश ने मुझे पूरी तरह भिगो दिया।

डाकचौकी पर पहुँचते ही सबसे पहला काम था – कपड़े बदलना और

दूसरा – चाय का ऑर्डर देना।

“ऐ

दून्या!” चौकीदार चीखा, “समोवार रख और

मलाई ले आ।” इतना सुनते ही दीवार के पीछे से लगभग चौदह साल

की एक लड़की बाहर निकली और आँगन की ओर दौड़ गई। उसकी सुन्दरता को देख मैं स्तब्ध रह

गया।

“क्या यह

तुम्हारी बेटी है?” मैने चौकीदार से पूछ लिया।

“बेटी है,” कुछ स्वाभिमान मिश्रित गर्व से

उसने उत्तर दिया। “हाँ, इतनी समझदार,

इतनी चंचल है, बिल्कुल अपनी स्वर्गवासी माँ पर

गई है।”

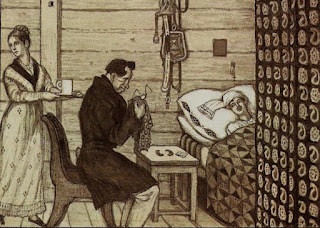

अब वह अपने

रजिस्टर में मेरे सफ़रनामे की जानकारी लिखने लगा, और मैं उसकी छोटी-सी मगर साफ़-सुथरी झोंपड़ी की दीवारों पर टँगी तस्वीरें

देखने लगा। तस्वीरें थीं पथभ्रष्ट पुत्र के बारे में। पहली तस्वीर में टोपी पहने

एक बुज़ुर्ग उत्साहपूर्वक अपने पुत्र को बिदा करता दिखाया गया था। पुत्र बिना देर

किए पिता का आशीर्वाद और रुपयों से भरी थैली लेता है। दूसरे चित्र में चटख रंगों

में नौजवान आदमी के पतन का किस्सा था। वह मेज़ पर बैठा है, झूठे

चापलूस मित्रों और बेशर्म औरतों से घिरा हुआ। अगली तस्वीर में निर्धन हो चुका

नौजवान एक कमीज़ और तिकोनी टोपी पहने सूअर चराता और उन्हीं के बीच भोजन करता दिखाया

गया था। उसके चेहरे पर गहरी पीड़ा एवम् पश्चात्ताप के लक्षण दिखाई दे रहे थे। अन्त

में चित्रित थी पिता के पास उसकी वापसी। सहृदय बूढ़ा वही कोट और टोपी पहने बाँहे

फैलाए उसकी ओर भाग रहा है। पथभ्रष्ट बेटा घुटनों के बल खड़ा है। पृष्ठभूमि में

रसोइया मोटी-तगड़ी भेड़ को काट रहा है, तो बड़ा भाई नौकर से इस

आनन्दोत्सव का कारण पूछ रहा है। हर तस्वीर के नीचे सुन्दर जर्मन कविताएँ लिखी थीं।

यह सब आज भी मेरे दिमाग़ में ताज़ा है – फूलों के गमले,

फूलदार परदों वाली चारपाई जैसी अन्य चीज़ों को भी मैं भूला नहीं हूँ।

याद है गृहस्वामी की – लगभग पचास वर्ष का फुर्तीला, तरोताज़ा तबियत का बूढ़ा, लम्बा हरा कुर्ता पहने जिस

पर फीतों से तीन मेडल लटके हुए थे।

मैं अभी अपने

पुराने कोचवान का हिसाब कर ही रहा था कि समोवार लिए दून्या आ धमकी। उस जवान,

शोख़ लड़की ने दूसरी ही नज़र में भाँप लिया कि उसका मुझ पर क्या प्रभाव

पड़ा है। उसने अपनी बड़ी-बड़ी नीली आँखें झपकाईं। मैं उससे बातें करने लगा। वह बेझिझक

मेरे प्रश्नों के उत्तर दे रही थी, जैसे कि उसने भी दुनिया

देखी है। उसके पिता को मैंने शराब का प्याला पेश किया, दून्या

को चाय दी और हम तीनों इस तरह बातें करने लगे मानो सदियों से एक-दूसरे को जानते

हों।

घोड़े कब से

तैयार थे,

मगर चौकीदार एवम् उसकी बेटी से बिदा लेने का मेरा मन ही नहीं हो रहा

था। आख़िरकार मैंने उनसे बिदा ली। पिता ने मेरी यात्रा शुभ होने की कामना की। बेटी

मुझे गाड़ी तक छोड़ने आई। ड्योढ़ी में मैं रुका और उसका चुम्बन लेने की अनुमति माँगी।

दून्या राज़ी हो गई…अनेक चुम्बन गिनवा सकता हूँ, जब से मैं यह सब करने लगा, मगर उनमें से एक भी इस

चुम्बन जैसा दीर्घ, इतना प्यारा प्रभाव मुझ पर न छोड़ सका।

अनेक वर्ष बीत

गए,

और परिस्थितियाँ मुझे फिर उसी मार्ग पर, उन्हीं

स्थानों पर ले आईं। मुझे बूढ़े चौकीदार और उसकी बेटी की याद आ गई और यह सोचकर मैं

ख़ुश हुआ कि दुबारा उसे देख सकूँगा। मगर, मैंने सोचा, हो सकता है कि बूढ़े चौकीदार का तबादला हो गया हो, शायद

दून्या की शादी हो गई हो। उनमें से किसी एक की मृत्यु का ख़याल भी मेरे मन में आया

और मैं आशंकित होकर डाकचौकी के निकट आया।

घोड़े डाकचौकी के

पास रुक गए। कमरे में घुसते ही मैं पथभ्रष्ट पुत्र की कहानी वाली तस्वीरों को

पहचान गया। मेज़ और चारपाई भी पुराने स्थानों पर ही रखे थे,

मगर खिड़कियों में अब फूल नहीं थे और हर चीज़ बेजान, बदरंग नज़र आ रही थी। चौकीदार मोटा कोट ओढ़े सो रहा था। मेरे आगमन ने उसे

जगा दिया। वह उठकर खड़ा हो गया…यह बिल्कुल सैम्सन वीरिन ही था,

मगर वह कितना बूढ़ा हो गया था! जिस वक्त वह अपने रजिस्टर में मेरा

सफ़रनामा लिखने की तैयारी कर रहा था, मैं उसके सफ़ेद बालों,

बढ़ी हुई दाढ़ी वाले चेहरे पर उभर आई गहरी झुर्रियों और झुकी हुई कमर

की ओर देखता रहा और अचरज किए बिना न रह सका कि केवल तीन या चार वर्षों के अन्तराल

ने एक हट्टे-कट्टे आदमी को किस कदर जर्जर और बूढ़ा बना दिया था।

“तुमने

मुझे पहचाना?” मैंने उससे पूछा। “हम तो

पुराने परिचित हैं।”

“हो सकता

है,” उसने बड़ी संजीदगी से उत्तर दिया। “यह रास्ता काफ़ी बड़ा है, कितने ही मुसाफ़िर मेरे यहाँ

आते-जाते रहते हैं।”

“तुम्हारी

दून्या अच्छी तो है?” मैं कहता रहा। बूढ़े ने नाक-भौंह चढ़ा

ली। “ख़ुदा जाने,” उसने जवाब दिया।

“शायद,

शादी हो गई है उसकी।” मैंने कहा।

बूढ़े ने यूँ

जताया जैसे कि उसने मेरी बात सुनी ही न हो और फुसफुसाकर मेरा सफ़रनामा पढ़ता रहा।

मैंने प्रश्नों की बौछार रोककर चाय लाने की आज्ञा दी। उत्सुकता ने मुझे परेशान

करना शुरू कर दिया था और मुझे उम्मीद थी कि शराब के एक दौर से मेरे पुराने परिचित

की ज़ुबान खुल जाएगी।

मैं ग़लत नहीं

था। बूढ़े ने पेश किए गए गिलास को लेने से इनकार नहीं किया। मैंने देखा कि ‘रम’ ने उसकी संजीदगी को भगा दिया है। दूसरा गिलास

पीते-पीते वह बतियाने लगा। वह अब या तो मुझे पहचान गया था या पहचानने का नाटक कर

रहा था, और उससे मुझे वह किस्सा सुनने को मिला जिसने मुझे

हिलाकर रख दिया।

“तो,

आप मेरी दून्या को जानते थे?” उसने शुरुआत की।

“कौन नहीं जानता था उसे? आह, दून्या, दून्या! क्या बच्ची थी! जो भी आता, तारीफ़ ही करता, कोई भी दोष न निकालता। मालकिनें उसे

कभी रूमाल, तो कभी कानों की बालियाँ देतीं। मालिक लोग

जानबूझकर रुक जाते, जैसे दोपहर या रात का भोजन करना चाहते

हों। मगर असल में सिर्फ इसलिए कि उसे ज़्यादा देर तक देख सकें। कोई मालिक कितना भी

गुस्से में क्यों न हो, उसे देखते ही शान्त हो जाता, और मुझसे भी प्यार से बातें करने लगता। यकीन कीजिए, साहब,

पत्रवाहक या सेना के सन्देशवाहक तो उससे आधा-आधा घण्टे तक बतियाते

रहते। घर तो उसी के भरोसे था। क्या लाना है, क्या बनाना है,

सभी कुछ कर लेती थी। और मैं, बूढ़ा मूरख,

उसे देख-देख अघाता न था। ख़ुश होता रहता। क्या मैं अपनी दून्या को

प्यार न करता था? क्या मैं उसकी देखभाल नहीं करता था?

क्या उसका जीना यहाँ दूभर हो गया था? नहीं,

मुसीबतों से कोई बच नहीं सकता। भाग्य का लिखा मिट नहीं सकता।”

अब उसने विस्तार

से अपना दुखड़ा सुनाया: तीन साल पहले जाड़े की एक शाम को,

जब चौकीदार नए रजिस्टर में लाइनें खींच रहा था और उसकी बेटी दीवार

के पीछे बैठी सिलाई कर रही थी, एक त्रोयका रुकी और रोयेंदार

टोपी, फ़ौजी कोट और शॉल ओढ़े एक मुसाफ़िर ने अन्दर आकर घोड़े

माँगे। घोड़े थे ही नहीं। इतना सुनते ही मुसाफ़िर ने आवाज़ ऊँची कर अपना चाबुक

निकाला। मगर दून्या, जो ऐसे दृश्यों की आदी थी, फ़ौरन दीवार के पीछे से भागकर आई और प्यारभरे स्वर में मुसाफ़िर से पूछने

लगी कि उसे कुछ खाने को तो नहीं चाहिए। दून्या के आगमन का अपेक्षित असर पड़ा।

मुसाफ़िर का गुस्सा छू मंतर हो गया। वह घोड़ों का इंतज़ार करने पर राज़ी हो गया और

उसने अपने लिए भोजन लाने को कहा। गीली, रोयेंदार टोपी उतारने

के बाद, शॉल हटाने के बाद और कोट उतारने के बाद प्रतीत हुआ

कि मुसाफ़िर एक जवान, हट्टा-कट्टा, सुडौल,

काली छोटी-छोटी मूँछों वाला घुड़सवार दस्ते का अफ़सर है। वह चौकीदार

के निकट पसर कर बैठ गया और बड़ी प्रसन्नता से उससे और उसकी बेटी से बतियाने लगा।

भोजन परोसा गया। इसी बीच घोड़े भी लौट आए और चौकीदार ने आज्ञा दी, कि उन्हें फ़ौरन, बिना दाना-पानी दिए, मुसाफ़िर की गाड़ी से जोत दिया जाए। मगर जब वह अन्दर आया तो उसने देखा,

कि नौजवान वहीं, बेंच पर लगभग बेहोश होकर लुढ़क

गया है। उसकी तबियत बिगड़ गई थी। सिर दर्द के मारे फ़टा जा रहा था। आगे जाना संभव

नहीं था…क्या किया जाए। चौकीदार ने अपनी चारपाई उसे दे दी और

यह तय किया गया कि यदि मरीज़ की हालत नहीं सुधरी तो अगली सुबह शहर से डॉक्टर बुलाया

जाए।

दूसरे दिन अफ़सर

की तबियत और बिगड़ गई। उसका नौकर घोड़े पर सवार होकर शहर से डॉक्टर बुलाने के लिए

रवाना हो गया। दून्या ने सिरके में भीगे रूमाल से उसका सिर बाँध दिया और अपनी

सिलाई लेकर उसकी चारपाई के पास बैठ गई। चौकीदार की उपस्थिति में मरीज़ एक भी शब्द

बोले बिना सिर्फ कराह रहा था। हालाँकि वह दो कप कॉफ़ी पी गया और कराहते हुए उसने

दोपहर के भोजन का आदेश भी दे दिया। दून्या उसके निकट से बिल्कुल नहीं हटी। हर पल

वह कुछ पीने की माँग करता और दून्या अपने हाथ से बनाए गए नींबू के शरबत का प्याला

उसे थमा देती। मरीज़ अपने होंठ गीले करता और हर बार गिलास वापस करते समय आभार प्रकट

करने के लिए अपने कमज़ोर हाथों में दून्या का हाथ ले लेता। भोजन के समय तक डॉक्टर

भी आ गया। उसने मरीज़ की नब्ज़ देखी। उसके साथ जर्मन में बातें कीं और रूसी में सबको

बताया कि उसे सिर्फ आराम की ज़रूरत है और दो दिन बाद वह जा सकता है। अफ़सर ने डॉक्टर

को फ़ीस के तौर पर पच्चीस रूबल दिए और उसे भोजन का निमन्त्रण दे डाला। डॉक्टर मान

गया। दोनों ने छक कर खाया, ‘वाइन’ की पूरी बोतल खाली कर दी और अत्यन्त प्रसन्नतापूर्वक एक-दूसरे से बिदा ली।

एक और दिन के

बाद अफ़सर बिल्कुल ठीक हो गया। वह बहुत ख़ुश था। लगातार दून्या अथवा चौकीदार के साथ

मज़ाक करता, सीटी बजाता, मुसाफ़िरों

से बातें करता, उनके सफ़रनामे को रजिस्टर में लिखता और उस भले

चौकीदार को उससे इतना प्यार हो गया कि तीसरी सुबह जब वह बिदा लेने लगा तो चौकीदार

का मन भर आया।

इतवार का दिन था,

दून्या चर्च जाने की तैयारी कर रही थी। अफ़सर को गाड़ी दी गई। उसने

चौकीदार से बिदा ली। वहाँ ठहराने एवम् स्वागत सत्कार के लिए उसे भरपूर इनाम दिया।

दून्या से भी बिदा ली और उसे चर्च तक, जो गाँव के छोर पर था,

गाड़ी में छोड़ देने की दावत दी। दून्या सोच में पड़ गई…”डरती क्यों है?” पिता ने उससे कहा, “मालिक कोई भेड़िया तो है नहीं जो तुझे खा जाएँगे। चर्च तक घूम आ।”

दून्या गाड़ी में

अफ़सर की बगल में बैठ गई। नौकर उछलकर पायदान पर चढ़ गया। कोचवान ने सीटी बजाई और

घोड़े चल पड़े।

बेचारा चौकीदार

समझ नहीं पाया कि अपनी दून्या को अफ़सर के साथ जाने की इजाज़त उसने ख़ुद ही कैसे दे

दी थी। वह कुछ देख क्यों नहीं पाया! उस समय उसकी बुद्धि को क्या हो गया था! आधा

घण्टा भी नहीं बीता होगा कि उसके दिल में दर्द होने लगा। वह इतना बेचैन हो गया कि

स्वयम् पर काबू न रख पाया और गिरजे की ओर चल पड़ा। गिरजे के निकट पहुँचने पर उसने

देखा कि लोग अपने-अपने घरों को जा चुके हैं, मगर

दून्या न तो ड्योढ़ी में दिखाई दी, न ही प्रवेश-द्वार के पास।

वह शीघ्रता से चर्च में घुसा। पादरी प्रतिमा के निकट से बाहर आ रहा था, सेवक मोमबत्तियाँ बुझा रहा था। कोने में बैठी दो बूढ़ी औरतें अभी तक

प्रार्थना कर रही थीं। मगर दून्या का वहाँ नामोनिशान न था। बेचारे पिता ने बड़ी

कठिनाई से सेवक से दून्या के बारे में यह पूछने का फ़ैसला किया कि वह वहाँ आई थी या

नहीं। उसे उत्तर मिला कि नहीं आई थी। चौकीदार अधमरा-सा होकर घर लौटा। सिर्फ एक

उम्मीद बाकी थी। हो सकता है, जवानी की चंचलता में दून्या ने

अगली डाकचौकी तक जाने का फ़ैसला किया हो, जहाँ उसकी धर्ममाता

रहती थी। पीड़ाभरी परेशानी से वह उस त्रोयका के वापस आने का इंतज़ार करने लगा जिसमें

उसने बेटी को भेजा था। कोचवान था कि लौटने का नाम ही नहीं ले रहा था। आख़िरकार शाम

को वह वापस लौटा– अकेला और बदहवास, दुर्भाग्यपूर्ण

सन्देश के साथ, “दून्या अफ़सर के साथ अगली डाकचौकी से आगे चली

गई।”

बूढ़ा इस आघात को

बर्दाश्त न कर पाया। वह फ़ौरन उसी चारपाई पर गिर पड़ा जिस पर पिछली रात नौजवान फ़रेबी

सोया था। अब, सारी बातों पर गौर करने के पश्चात्

चौकीदार भाँप गया कि उसकी बीमारी बनावटी थी। वह ग़रीब तेज़ बुखार में जलने लगा। उसे

शहर ले जाया गया और उसके स्थान पर दूसरा चौकीदार कुछ समय के लिए नियुक्त किया गया।

उस अफ़सर का इलाज करने वाले डॉक्टर ने बूढ़े चौकीदार का भी इलाज किया। उसने चौकीदार

को विश्वास दिलाया कि नौजवान एकदम तन्दुरुस्त था, और वह तभी

उसकी बुरी नीयत को भाँप गया था। मगर उसके चाबुक के डर से चुप रहा। या तो वह जर्मन

सच बोल रहा था, या अपनी दूरदर्शिता की शेख़ी बघार रहा था। मगर

उसके कथन से बेचारे मरीज़ को ज़रा भी सान्त्वना न मिली। बीमारी से कुछ सँभलते ही

चौकीदार ने डाकचौकी के बड़े अफ़सर से दो माह की छुट्टी माँगी और अपने इरादों के बारे

में किसी को एक भी शब्द बताए बिना पैदल ही अपनी बेटी की खोज में चल पड़ा। रजिस्टर

देखकर उसने पता लगाया कि घुड़सवार दस्ते का वह अफ़सर मीन्स्की स्मोलेन्स्क से

पीटरबुर्ग जा रहा था। जो कोचवान उसे ले गया था उसने बताया, कि

दून्या पूरे रास्ते रोती रही थी, हालाँकि ऐसा प्रतीत हो रहा

था जैसे वह अपनी इच्छा से जा रही हो।

‘ईश्वर

ने चाहा तो’, चौकीदार ने सोचा, ‘मैं

अपनी भटकी हुई भेड़ को वापस ले आऊँगा’। यह विचार करते-करते वह

पीटर्सबुर्ग पहुँचा। इजमाइलोव्स्की मोहल्ले में अपने पुराने परिचित, सेना के रिटायर्ड अंडर ऑफिसर के यहाँ रुका और अपनी तलाश जारी रखी। शीघ्र

ही उसने पता लगाया कि घुड़सवार दस्ते का वह अफ़सर पीटर्सबुर्ग में ही है, और देमुतोव सराय के निकट रहता है। चौकीदार ने उसके घर जाने का निश्चय

किया। पौ फटते ही वह उसके मेहमानख़ाने में दाखिल हुआ और हुज़ूर की ख़िदमत में ये

दरख़्वास्त की, कि एक बूढ़ा सिपाही उनसे मिलना चाहता है।

अर्दली ने, जो कुँए के पास जूते साफ़ कर रहा था, कहा कि साहब सो रहे हैं और वे ग्यारह बजे से पहले किसी से नहीं मिलते।

चौकीदार चला गया और निर्धारित समय पर वापस आया। मीन्स्की स्वयम्, लाल टोपी पहने, बाहर आया।

“क्यों

भाई, क्या चाहते हो?” उसने पूछा।

बूढ़े का दिल भर

आया। उसकी आँखों से आँसू बह निकले और थरथराती आवाज़ में उसने सिर्फ इतना कहा,

“हुज़ूर!।।मेहरबानी कीजिए!।।” मीन्स्की ने फ़ौरन

उसकी ओर देखा, चीख़ा, उसका हाथ पकड़कर

अपने अध्ययन-कक्ष में ले आया और अपने पीछे दरवाज़ा बंद कर दिया। “हुज़ूर!…” बूढ़ा कहता गया, “गाड़ी

से गिरा दाना धूल में मिल जाता है, कम-से-कम मुझे मेरी ग़रीब

दून्या तो दे दीजिए! आपका दिल तो उससे भर गया होगा, उसे यूँ

ही न मारिए!”

“जो हो

चुका है, उसे लौटाया नहीं जा सकता,” नौजवान

ने भावावेश में कहा। “मैं तुम्हारा गुनहगार हूँ और तुमसे

माफ़ी माँगता हूँ, मगर ऐसा न सोचना कि मैं दून्या को छोड़

दूँगा। वह ख़ुश रहेगी, मैं वादा करता हूँ। तुम्हें उसकी ज़रूरत

क्यों है? वह मुझसे प्यार करती है, वह

अपने पुराने जीवन को भूल चुकी है। जो कुछ हो गया है, उसे न

तो तुम भूल पाओगे और न वह भूल सकेगी।” फिर उसके हाथ की

आस्तीन में कुछ घुसेड़ते हुए, उसने दरवाज़ा खोला और इससे पहले

कि चौकीदार कुछ समझता, उसने अपने आप को रास्ते पर पाया।

बड़ी देर तक वह

निश्चल खड़ा रहा। अन्त में उसने देखा कि उसकी आस्तीन में एक लिफ़ाफ़ा है,

उसने उसे खोला और उसे दिखाई दिए पाँच-पाँच, दस-दस

के कुछ मुड़े-तुड़े नोट। उसकी आँखों से फिर आँसू बह चले – अपमान

के आँसू। उसने उन नोटों को ज़ोर से भींचा। उन्हें ज़मीन पर फेंका। जूतों से रौंदा और

चल पड़ा।

कुछ कदम आगे

जाने के बाद वह रुका। कुछ सोचने लगा…और वापस

लौटा।।मगर अब वहाँ नोट थे ही नहीं। शानदार कपड़े पहने एक नौजवान, उसे देखते ही, गाड़ी की ओर भागा, उछलकर गाड़ी में चढ़ गया और चिल्लाया, “चलो!” चौकीदार ने उसका पीछा नहीं किया। उसने वापस अपनी डाकचौकी पर लौटने का

निश्चय कर लिया। मगर जाने से पहले कम-से-कम एक बार अपनी बेचारी दून्या को देखना

चाहता था। इस उद्देश्य से दो दिनों के बाद वह फिर मीन्स्की के घर आया, मगर अर्दली ने बड़ी गंभीरता से उत्तर दिया कि मालिक किसी से नहीं मिलते और

उसका गिरहबान पकड़कर, उसे मेहमानख़ाने से बाहर धकेलकर, धड़ाम् से दरवाज़ा बन्द कर दिया। चौकीदार खड़ा रहा, खड़ा

रहा और वापस चला गया।

उसी शाम वह

गिरजे से प्रार्थना करके लितेयनाया रास्ते पर जा रहा था। अचानक उसके सामने से एक

शानदार बग्घी गुज़री और चौकीदार ने उसमें बैठे मीन्स्की को पहचान लिया। बग्घी एक

तिमंज़िले भवन के प्रवेश-द्वार के ठीक सामने रुकी और अफ़सर अंदर घुस गया। चौकीदार के

दिमाग़ में एक ख़ुशनुमा ख़याल तैर गया। वह वापस मुड़ा और कोचवान के निकट आकर पूछने लगा,

“किसका घोड़ा है, भाई? कहीं

मीन्स्की का तो नहीं?”

“ठीक

पहचाना”, कोचवान ने जवाब दिया, “मगर

तुम्हें इससे क्या?”

“ऐसी बात

है : तुम्हारे मालिक ने मुझे यह चिट्ठी उनकी दून्या को देने के लिए कहा था,

मगर मैं तो भूल ही गया कि दून्या रहती कहाँ है?”

“यहीं,

दूसरी मंज़िल पर। तुम अपनी चिट्ठी बड़ी देर से लाए, भैया, अब तो वह ख़ुद ही उसके पास आए हैं।”

“कोई बात

नहीं”, धड़कते दिल से चौकीदार ने कहा। “शुक्रिया,

बताने के लिए। मैं अपना काम कर लूँगा।” इतना

कहकर वह सीढ़ियाँ चढ़ने लगा।

दरवाज़ा बंद था।

उसने घण्टी बजाई। कुछ क्षण तनावपूर्ण इंतज़ार में बीते। चाभी घुमाने की आवाज़ आई।

दरवाज़ा खुला।

“अव्दोत्या

सम्सानोव्ना यहाँ रहती हैं?” उसने पूछा।

“हाँ,

यहीं”, जवान नौकरानी ने जवाब दिया। “तुम्हें उनकी क्या ज़रूरत है?”

चौकीदार बिना

जवाब दिए हॉल में घुसा।

“नहीं,

नहीं”, पीछे-पीछे नौकरानी चिल्लाई, “अव्दोत्या सम्सानोव्ना के पास मेहमान हैं।”

मगर चौकीदार

बिना सुने आगे बढ़ता गया। पहले दो कमरों में अँधेरा था,

तीसरे में रोशनी थी। वह खुले हुए दरवाज़े के निकट पहुँच कर रुक गया।

सलीके से सजाए गए कमरे में सोच में डूबा हुआ मीन्स्की बैठा था। दून्या, आधुनिकतम ढंग से सजी सँवरी, उसकी कुर्सी के हत्थे पर

यूँ बैठी थी, मानो अपने अंग्रेज़ी घोड़े पर बैठी हो। वह बड़े

प्यार से मीन्स्की की ओर देखती हुई अपनी जगमगाती उँगलियों से उसके बालों से खेल

रही थी। बेचारा चौकीदार! अपनी बेटी उसे कभी भी इतनी सुंदर प्रतीत नहीं हुई थी। वह

ठगा सा उसकी ओर देखता रहा।

“कौन है?”

उसने बिना सिर उठाए पूछा। वह ख़ामोश रहा। कोई जवाब न पाकर दून्या ने

सिर उठाया…और चीख़ मारकर कालीन पर गिर पड़ी। भयभीत मीन्स्की

उसे उठाने के लिए आगे बढ़ा और अचानक दरवाज़े पर बूढ़े चौकीदार को देखकर, दून्या को वहीं छोड़कर गुस्से से काँपता हुआ उसकी ओर बढ़ा।

“क्या

चाहते हो तुम?” उसने दाँत पीसते हुए कहा, “हर जगह मेरा पीछा क्यों कर रहे हो, डाकू की तरह?

क्या मुझे मार डालना चाहते हो? भाग जाओ!”

और उसने अपने मज़बूत हाथ से बूढ़े का गिरहबान पकड़कर उसे सीढ़ियों से

धकेल दिया।

बूढ़ा अपने कमरे

पर आया। मित्र ने उसे अदालत में फ़रियाद करने की सलाह दी,

मगर चौकीदार ने कुछ सोचकर हाथ झटक दिए और पीछे हटने की ठान ली। दो

दिनों बाद वह पीटर्सबुर्ग से अपनी डाकचौकी पर वापस आया और अपनी नौकरी करने लगा।

“दो साल

बीत गए,” उसने बात ख़त्म करते हुए कहा, “मैं दून्या के बगैर रह रहा हूँ, और उसकी कोई ख़बर

नहीं है। ज़िन्दा है या मर गई, ख़ुदा जाने। कुछ भी हो सकता है।

न तो वह ऐसी पहली लड़की है और न ही आख़िरी जिसे कि एक मुसाफ़िर फुसला कर भगा ले गया

और कुछ दिनों तक अपने पास रखकर फिर छोड़ दिया। पीटर्सबुर्ग में ऐसी बेवकूफ़ नौजवान

लड़कियाँ कई हैं, जो आज मखमली पोशाक में हैं, तो कल पैबन्द लगे कपड़ों में सड़क पर झाडू लगाती दिखाई देती हैं। जब मैं

सोचता हूँ, कि शायद दून्या का भी यही हश्र होगा, तो अनजाने ही उसकी मृत्यु की कामना करने लगता हूँ…”

यह थी मेरे

परिचित बूढ़े चौकीदार की कहानी, जिसमें कई बार उन

आँसुओं ने विघ्न डाला था, जिन्हें वह अपने कुर्ते की बाँह से

यूँ पोंछता था जैसे कि वह दिमित्रियेव की सुंन्दर लोककथा का नायक तेरेंतिच हो। ये

आँसू उस शराब के परिणामस्वरूप भी बह रहे थे जिसके पाँच गिलास वह कहानी

सुनाते-सुनाते गटक गया था। वैसे चाहे जो भी हो, इस कहानी ने

मेरे दिल पर गहरा असर डाला। उससे बिदा लेने के बाद भी मैं कई दिनों तक बूढ़े

चौकीदार को भूल न सका। गरीब बेचारी दून्या के बारे में सोचता रहा।

कुछ ही दिन पहले,

शहर से गुज़रते हुए मुझे अपने दोस्त की याद आई। पता चला कि जिस

डाकचौकी पर वह काम करता था, वह अब नहीं रही। मेरे इस सवाल का

कि “क्या बूढ़ा चौकीदार ज़िन्दा है?” कोई

भी सन्तोषजनक उत्तर न मिला। मैंने उस इलाके में जाने का निश्चय कर लिया और घोड़े

लेकर उधर ही गाँव की ओर चल पड़ा। यह शिशिर ऋतु की बात थी। आसमान मटमैले बादलों से

घिरा था। नंगे खेतों से होकर, अपने साथ लाल-पीले पत्ते

बटोरती हुए ठण्डी हवा बह रही थी। मैं गाँव में सूर्यास्त के समय पहुँचा और डाकचौकी

के निकट रुका। ड्योढ़ी में (जहाँ बेचारी दून्या ने कभी मेरा चुम्बन लिया था) एक

मोटी औरत आई और मेरे सवालों के जवाब में बोली कि बूढ़ा चौकीदार तकरीबन साल भर पहले

मर गया था और उसके घर में एक शराब बनाने वाला रहता है। और वह उसी शराब-भट्टीवाले

की बीबी है। मुझे अपनी इस निरर्थक यात्रा और फिज़ूल ही खर्च किए गए सात रूबल्स पर

दुख हो रहा था।

“वह कैसे

मरा?” मैंने शराब-भट्टीवाले की बीबी से पूछ ही लिया।

“पी-पीकर…”

वह बोली।

“उसे

कहाँ दफ़नाया है?”

“बस्ती

के बाहर, उसकी बीबी की बगल में।”

”क्या

मुझे उसकी कब्र तक ले जा सकती हो?”

“क्यों

नहीं। ऐ, वान्का! बस, खेल हो गया शुरू

बिल्ली से! मालिक को कब्रिस्तान ले जा और चौकीदार की कब्र दिखा दे।”

इतना सुनते ही

फटे-पुराने कपड़े पहने लाल बालोंवाला, झुकी

हुई कमरवाला एक बालक मेरे पास दौड़कर आया और फ़ौरन मुझे बस्ती के बाहर ले गया।

“तुम

मृतक को जानते थे?” उससे रास्ते में यूँ ही पूछ लिया था।

“कैसे

नहीं जानता। उसने मुझे गुलेल बनाना सिखाया था…शराबख़ाने से

लौटता और हम उसके पीछे-पीछे, चिल्लाते “दादा-दादा! अखरोट!” और वह हमें अखरोट देता। हमेशा

हमारे साथ ही घूमता।”

“मुसाफ़िर

उसे याद करते हैं?”

“अब तो

मुसाफ़िर कम ही आते हैं। मुसाफ़िर ख़ास तौर से इस तरफ़ क्यों मुड़ेगा, और मृतकों से किसी को क्या मतलब है…गर्मियों में एक

मालकिन आई थी, उसने बूढ़े चौकीदार के बारे में पूछा था और

उसकी कब्र पर भी गई थी।”

“कैसी

मालकिन?” मैंने उत्सुकता से पूछा।

“सुंन्दर-सी

मालकिन”, बालक बोला। “छह घोड़ोंवाली

गाड़ी में आई थी। तीन नन्हे-मुन्नों और आया के साथ। चेहरे पर काला नकाब डाले हुए।

और जैसे ही उसे बताया कि बूढ़ा चौकीदार गुज़र चुका है, वह रो

पड़ी और बच्चों से बोली, “चुपचाप बैठे रहो, मैं कब्रिस्तान हो आती हूँ।” उसे मैं ले ही जा रहा

था मगर मालकिन बोली, “मुझे रास्ता मालूम है।” और उसने मुझे चान्दी का पाँच कोपेक का सिक्का दिया।”

हम कब्रिस्तान

पहुँचे। सूनी जगह। कोई बाड़ नहीं। लकड़ी के सलीबों से अटी। एक भी पेड़ की छाया नहीं।

ज़िंन्दगी में कभी मैंने इतना दयनीय कब्रिस्तान नहीं देखा था।

“यह है

बूढ़े चौकीदार की कब्र,” रेत के एक ढेर पर चढ़कर बच्चा बोला,

जिस पर ताँबे की प्रतिमा जड़ा काला सलीब खड़ा था।

“मालकिन

यहाँ आई थी?” मैंने पूछा।

“आई थी”,

वान्का ने जवाब दिया। “मैं उसे दूर से देख रहा

था। वह यहाँ खड़ी रही बड़ी देर तक। फिर गाँव में जाकर पादरी को बुला लाई। उसे पैसे

दिए और चली गई। और मुझे दिया चाँदी का सिक्का। अच्छी थी मालकिन।”

और मैंने भी

बच्चे को पाँच कोपेक का एक सिक्का दिया। अब मुझे न इस यात्रा का गम था और न उन सात

रूबल्स का जो दरअसल मैंने इस पर खर्च किए थे।

Story - The Stationmaster / Alexander Pushkin

Fiscal

clerk-of-registration, Despot of the posting station.

Who has not cursed

stationmasters? Who has not quarreled with them frequently? Who has not

demanded the fateful book from them in moments of anger, in order to enter in

it a useless complaint against their highhandedness, rudeness, and negligence?

Who considers them anything but a blemish on the human race, as bad as the

chancery clerks of yore or at least as the robbers of the Murom Forest? Let us

be fair, however, and try to imagine ourselves in their position: then,

perhaps, we shall judge them with more lenience. What is a stationmaster? A

veritable martyr of the fourteenth class, whose rank is enough to shield him

only from physical abuse, and at times not even from that. (I appeal to my

reader's conscience What are the duties of this despot, as PrinceViazemskii

playfully calls him? Are they not tantamount to penal servitude? Day or night,

he does not have a moment's quiet. The traveler takes out on him all the

irritation accumulated during a tedious ride. Should the weather be unbearable,

the highway abominable, the coachdriver intractable, should the horses refuse

to pull fast enough--it is all the stationmaster's fault. Entering the

stationmaster's poor abode, the traveler looks on him as an enemy; the host is

lucky if he can get rid of his unwanted guest fast, but what if he happens to

have no horses available? God! What abuses, what threats shower on his head! He

is obliged to run about the village in rain and slush; he will go out on his

porch even in a storm or in the frost of the twelfth day of Christmas just to

seek a moment's rest from the shouting, pushing, and shoving of exasperated

travelers. A general arrives: the trembling stationmaster lets him have the

last two teams of horses, including the one that should be reserved for

couriers. The general rides off without a word of thanks. Five minutes have

scarcely gone by when bells tinkle and a state courier tosses his order for

fresh horses on the stationmaster's desk!... Let us try to comprehend all this

in full, and our hearts will be filled with sincere compassion instead of

resentment. Just a few more words: in the course of twenty years I have

traveled Russia in all directions; I know almost all the postal routes; I have

been acquainted with several generations of coachdrivers; it is a rare postmaster

whose face I do not recognize, and there are few I have not had dealings with.

In the not too distant future I hope to publish a curious collection of

observations I have made as a traveler; for now I will only say that

postmasters as a group are usually presented to the public in an unfair light.

These maligned public servants are usually peaceable people, obliging by

nature, inclined to be sociable, modest in their expectations of honors, and

not too greedy for money. From their conversations (which traveling gentlemen

are wrong to ignore) one can derive a great deal that is interesting and

instructive. For my part, I must confess that I would rather talk with them

than with some official of the sixth class traveling on government business.

It will not be

difficult to guess that I have some friends among the honorable estate of

stationmasters. The memory of one of them is indeed precious to me.

Circumstances drew us together at one time, and it is he of whom I now intend

to talk to my amiable readers.

In I 8 I 6, in the

month of May, I happened to be traveling through N.Guberniia, along a route

that has since been abandoned. Of low rank at the time, I traveled by post,

hiring two horses at each stagers As a result, stationmasters treated me with

little ceremony, and I often had to take by force what I thought should have

been given me by right. Being young and hotheaded, I felt indignant over the

baseness and pusillanimity of the stationmaster who gave away to some

high-ranking nobleman the team of horses that had been prepared for me. It also

took me a long time to get used to being passed over by a snobbish flunkey at

the able of a governor. Nowadays both the one and the other seem to me to be in

the order of things. Indeed what would become of us if the rule convenient to

all, "Let rank yield to rank," were to be replaced by some other,

such as "Let mind yield to mind"? What arguments would arise? And

whom would the butler serve first? But let me return to my story.

It was a hot day. When

we were still three versts away from the station of P. it started sprinkling,

and in a minute a shower drenched me to the skin. On my arrival at the station,

my first concern was to change into dry clothes as soon as possible, and the

second, to ask for some tea.

"Hey,

Dunia!" called out the stationmaster. "Light the samovar and go get

some cream." As these words were pronounced, a little girl aged about

fourteen appeared from behind the partition and ran out on the porch. I was

struck by her beauty.

"Is that your daughter?"

I asked the stationmaster.

"Aye, truly she

is," answered he, with an air of satisfaction and pride, "and what a

sensible, clever girl, just like her late mother."

He started copying out

my order for fresh horses, and I passed the time by looking at the pictures

that adorned his humble but neat dwelling. They illustrated the parable of the

Prodigal Son. In the first one, a venerable old man, in nightcap and dressing

gown, was bidding farewell to a restless youth who was hastily accepting his

blessing and a bag of money. The second one depicted the young man's lewd

behavior in vivid colors: he was seated at a table, surrounded by false friends

and shameless women. Farther on, the ruined youth, in rags and with a

three-cornered hat on his head, was tending swine and sharing their meal; 30

deep sorrow and repentance were reflected in his features. The last picture

showed his return to his father: the warmhearted old man, in the same nightcap

and dressing gown, was running forward to meet him; the Prodigal Son was on his

knees; in the background the cook was killing the fatted calf, and the elder

brother was asking the servants about the cause of all the rejoicings Under

each picture I read appropriate verses in German. All this has remained in my

memory to this day, together with the pots of balsam, the motley curtain of the

bed, and other surrounding objects. I can still see the master of the house

himself as if he were right before me: a man about fifty years of age, still

fresh and agile, in a long green coat with three medals on faded ribbons.

I had scarcely had

time to pay my driver for the last stage when Dunia was already returning with

the samovar. The little coquette only had to take a second glance at me to

realize what an impression she had made on me; she cast down her big blue eyes;

but as I started up a conversation with her she answered without the slightest

bashfulness, like a young woman who has seen the world. I offered a glass of

rum punch to her father and a cup of tea to her, and the three of us conversed

as if we had long been acquainted.

The horses had been

ready for quite some time but I did not feel like parting with the

stationmaster and his daughter. At last I said good-bye to them; the father

wished me a pleasant journey, and the daughter came to see me to the cart. On

the porch I stopped and asked her to let me kiss her; she consented... I have

accumulated many recollections of kisses but none has made such a lasting and

delightful impression on me as the one I received from Dunia.

Some years went by,

and circumstances brought me once more to the same places, along the same

route. I remembered the old stationmaster's daughter, and the thought of seeing

her again gave me joy. I told myself that the old stationmaster might well have

been replaced, and that Dunia was likely to have married. It even occurred to

me that one or the other might have died, and I approached the station with

rueful premonitions.

The horses stopped by

the small building of the station. As I entered the room, I immediately

recognized the pictures illustrating the parable of the Prodigal Son; the table

and the bed stood in their former places; but there were no longer any flowers

on the windowsills, and everything around betrayed dilapidation and neglect.

The stationmaster himself slept under a fur coat; my arrival woke him; he got

up... It was indeed Samson Vyrin, but how he had aged! While he set about

entering my order for horses, I looked at his gray hair, the deep furrows

lining his face, which had not been shaven for a long time, his hunched back,

and I could hardly believe that three or four years could have changed a

stalwart fellow into such a feeble old man.

"Do you recognize

me?" I asked him. "You and I are old acquaintances."

"That may well

be," he answered sullenly; "this is a busy highway; many travelers

come and go."

"How's your

Dunia?" I pursued the conversation. The old man frowned.

"God knows,"

he answered.

"So she's

married, is she? " I asked.

The old man pretended

not to have heard my question and continued muttering details of my travel

document. I refrained from further questions and had the kettle put on for tea.

Burning with curiosity, I hoped that some rum punch might loosen my old

acquaintance's tongue.

I was right; the old

man did not refuse the glass I offered him. The rum noticeably dissipated his

gloom. Over the second glass he became talkative: he either remembered me or

pretended to, and I heard from him, the following story,

which captured my

imagination and deeply moved me at the time.

"So you knew my

Dunia? " he began. "Aye, verily, who didn't know her? Oh, Dunia,

Dunia! What a fine lass she was! No matter who'd pass through here, in the old

days, they'd all praise her; no one ever said a word against her. The ladies would

give her presents, now a kerchief, now a pair of earrings. Gentlemen passing

through would deliberately stay on, as if to dine or sup, but really only to

look at her a little longer. It often happened that a gentleman, however angry

he was, would calm down in her presence and talk to me kindly. Faith, sir,

couriers, government emissaries, would converse with her for as long as half an

hour at a time. The whole household rested on her: be it cleaning or cooking,

she'd see to it all. And I, confound me for a fool, just doted on her, just did

not know how to treasure her enough; who'd dare say I didn't love my Dunia,

didn't cherish my child? Who had a good life if she didn't? But no, you cannot

drive off evil by curses: you cannot escape your fate."

He began telling me

about his grief in detail. Three years before, one winter evening when the

stationmaster was lining his new register with a ruler and Dunia was sewing a

dress behind the partition, a troika drove up, and a traveler, wearing a

Circassian hat and military coat, and wrapped in a scarf, came into the room

demanding horses. All the horses were out. Hearing this news, the traveler was

about to raise both his voice and his whip, but Dunia, who was used to such

scenes, ran out from behind the partition and sweetly asked the man if he would

like to have something to eat. Dunia's appearance produced its usual effect.

The traveler's anger dissipated; he agreed to wait for horses and ordered

supper. When he had taken off his wet shaggy hat, unwound his scarf, and thrown

off his coat, he turned out to be a slim young hussar with a little black

mustache. He made himself at home at the stationmaster's, and was soon merrily

conversing with him and his daughter. Supper was served. In the meanwhile some

horses arrived, and the stationmaster gave orders to harness them to the

traveler's carriage immediately, without even feeding them; but when he

returned to the house he found the young man lying on the bench almost

unconscious; he was feeling sick, he had a headache, he could not travel on...

What could you do? The stationmaster yielded his own bed to him, and it was

resolved that if he did not get any better by the morning, they would send to

the town of S. for the doctor.

The hussar felt even

worse the next day. His orderly rode to town to fetch the doctor. Dunia wrapped

a handkerchief soaked in vinegar around the hussar's head and sat by his bed

with her sewing. In the stationmaster's presence, the patient groaned and could

hardly utter a word; but he drank two cups of coffee nonetheless and, groaning,

ordered himself dinner. Dunia did not leave his bedside. He kept asking for

something to drink, and Dunia brought him a jug of lemonade prepared by her own

hand. The sick man took little sips, and every time he returned the jug to Dunia,

he squeezed her hand with his enfeebled fingers in token of gratitude. The

physician arrived by dinner time. He felt the patient's pulse and spoke with

him in German; in Russian he declared that all the sick man needed was rest,

and he would be well enough to continue his journey in a couple of days. The

hussar handed him twenty-five rubles in payment for his visit and invited him

to stay for dinner; the physician accepted; both ate with excellent appetite,

drank a bottle of wine, and parted highly satisfied with each other.

Another day passed,

and the hussar recovered entirely. He was extremely cheerful; joked

incessantly, now with Dunia, now with her father; whistled little tunes; talked

with the travelers; entered their orders in the postal register; and made

himself so agreeable to the warmhearted stationmaster that on the third day he

was sorry to part with his amicable lodger. It was a Sunday: Dunia was

preparing to go to mass. The hussar's carriage drove up. He took leave of the

stationmaster, generously rewarding him for his bed and board; he said goodbye

to Dunia, too, and offered to take her as far as the church, which was on the

edge of the village. Dunia stood perplexed.

"What are you

afraid of?" said her father. "His Honor's not a wolf; he won't eat

you: go ahead, ride with him as far as the church."

Dunia got into the

carriage next to the hussar, the orderly jumped up next to the driver, the

driver whistled, and the horses started off at a gallop.

Later the poor

stationmaster could not understand how he could have permitted Dunia to go off

with the hussar; what had blinded him? what had deprived him of reason? Half an

hour had scarcely passed when his heart began to ache and ache, and anxiety

overwhelmed him to such a degree that he could no longer resist setting out for

the church himself. He could see as he approached the church that the

congregation was already dispersing, but Dunia was neither in the churchyard

nor on the porch. He hurried into the church: the priest was leaving the altar,

the sexton extinguishing the candles, and two old women still praying in a

corner; but Dunia was not there. Her poor father could hardly bring himself to

ask the sexton if she had been to mass. She had not, the sexton replied. The

stationmaster went home more dead than alive. The only hope he had left was

that Dunia, with a young girl's capricious impulse, might have decided to ride

as far as the next station, where her godmother lived. He waited in a state of

harrowing agitation for the return of the team of horses that had driven her

off. But the driver did not come back for a long time. At last toward evening

he arrived, alone and drunk, with the appalling news: "Dunia went on with

the hussar past the next station."

The old man could not

bear his misfortune: right there and then, he took to the same bed in which the

young deceiver had lain the night before. Turning all the circumstances over in

his mind, he could now guess that the hussar had only feigned illness. The poor

old man developed a high fever; he was taken to S. and temporarily replaced by

another person at the station. The same physician who had been to see the

hussar was treating him. He assured the stationmaster that the young man had

been perfectly healthy, and that he, the doctor, had guessed his evil

intentions even then but had kept his silence, fearing the young man's whip.

Whether the German spoke the truth or just wished to boast of his foresight,

what he said certainly did not console the poor patient. The latter, having

scarcely recovered from his illness, asked the district postmaster in S. for a

two-month leave of absence, and without saying a word to anyone about his

intentions, set out on foot to find his daughter. He knew from the travel

document that Captain Minskii had been traveling from Smolensk to Petersburg.

The driver who had driven them said that Dunia had wept during the whole

journey, though it did seem that she was going of her own free will.

"Perchance,"

the stationmaster said to himself, "I shall bring my lost sheep

home."

He arrived in Petersburg

with this in mind, put up in the barracks of the Izmailovskii Regiment, at the

lodging of a retired noncommissioned officer who was a former comrade, and

began his search. He soon found out that Captain Minskii was in Petersburg and

lived at the Hotel Demuth. The stationmaster decided to call on him.

He presented himself

at the captain's anteroom early one morning and asked the orderly to announce

to His Honor that an old soldier begged to see him. The orderly, who was

cleaning a boot on a last, declared that his master was asleep, and that he

never received anybody before eleven o'clock. The stationmaster went away and

came back at the appointed time. Minskii himself came out to him in his

dressing gown and red skullcap.

"What can I do

for you, brother?" he asked.

The old man's heart

seethed with emotion, tears welled up in his eyes, and he could only utter in a

trembling voice, "Your Honor!... Do me the Christian favor!..."

Minskii took a quick

glance at him, flushed, seized him by the hand, led him to his study, and

locked the door.

"Your

Honor," continued the old man, "what is done cannot be undone but at

least give me back my poor Dunia. You have had your fun with her; do not ruin

her needlessly."

"What can't be

cured must be endured," said the young man in extreme embarrassment.

"I stand guilty before you and I ask for your pardon, but don't think I

could abandon Dunia: she will be happy, I give my word of honor. What would you

want her for? She loves me; she has grown away from her former station in life.

Neither you nor she could ever forget what has happened."

Then, thrusting

something into the cuff of the stationmaster's sleeve, he opened the door, and

the old man found himself on the street again, though he could not remember how

he had got there.

He stood motionless

for a long time; at last he took notice of a roll of some kind of paper in the

cuff of his sleeve; he pulled it out, and unrolling it, discovered several

crumpled five- and ten-ruble notes. Tears welled up in his eyes once more,

tears of indignation. He pressed the notes into a lump, threw them on the

ground, trampled on them with his heel, and walked away... Having gone a few

steps, however, he stopped, thought for a while... returned... but by then the

banknotes were gone. A well-dressed young man ran up to a cab as soon as he

noticed the stationmaster returning, got in quickly, and shouted:

"Go!" The stationmaster did not chase after him.47 He decided to

return home to his station, but before doing so, he wished to see his poor

Dunia just once more. To this end, he returned to Minskii after a couple of

days, but the orderly told him sternly that his master was not receiving

anybody, gave him a push with his chest to get him out of the anteroom, and

slammed the door in his face. The stationmaster stood there for a while, but

finally went away.

In the evening of that

same day, having attended service at the Church of All the Afflicted, he walked

along Liteinaia Street. Suddenly a garish droshky dashed by him, and he

recognized Minskii seated in it. It stopped before the entrance of a

three-story building, and the hussar ran up the steps. A felicitous thought

flashed through the stationmaster's mind. He walked back, and when he came

alongside the driver, he said:

"Whose horse is

this, my good man? Isn't it Minskii's?"

"Just so,"

answered the driver, "and what do you want? "

"Here's what:

your master gave me a note to take to his Dunia, but I went and forgot where

this Dunia lives."

"She lives right

here, on the second floor. But you're tardy with your note, brother: he himself

is up there now."

"No matter,'}

rejoined the stationmaster, with an inexpressible leap of the heart.

"Thanks for telling me, but I'll do my job anyway." With these words

he went up the stairs. The door was locked; he rang, and a few seconds of

painful anticipation followed. The clanking of a key could be heard, and the

door opened.

"Does Avdotia

Samsonovna live here?" he asked.

"Yes, she

does," answered the young maidservant. "What do you want with

her?" The stationmaster went through to the hall without answering.

"You can't, you mustn't!" shouted the maid after him. "Avdotia

Samsonovna has visitors."

But the stationmaster

pressed forward, paying no attention. The first two rooms were dark, but there

was a light in the third one. He walked up to the open door and stopped. In the

room, which was elegantly furnished, he saw Minskii seated, deep in thought.

Dunia, dressed in all the finery of the latest fashion, sat on the arm of his

easy chair like a lady rider on an English saddle. She was looking at Minskii

with tenderness, winding his dark locks around her fingers, which glittered

with rings. Poor stationmaster! Never had his daughter appeared so beautiful to

him; he could not help admiring her.

"Who is

there?" she asked without raising her head. He remained silent. Receiving

no answer, Dunia raised her head... and fell to the carpet with a shriek.

Minskii, alarmed, rushed to lift her up, but when he caught sight of the old

stationmaster standing in the doorway, he left Dunia and came up to him,

trembling with rage.

"What do you

want? " he hissed at him, clenching his teeth. "Why do you steal

after me like a brigand? Do you intend to cut my throat? Get out of here!"

and with his strong hand he grabbed the old man by the collar and flung him out

on the staircase.

The old man returned

to his lodgings. His friend advised him to file a complaint, but the station

master after considering the matter, gave it up as a lost cause and decided to

retreat. In another two days he left Petersburg for his post station, and took

up his duties once more.

"It's almost

three years now," he concluded, "that I've been living without Dunia,

having no news of her whatsoever. Whether she is alive or dead, God only knows.

Anything can happen. She is not the first, nor will she be the last, to be

seduced by some rake passing through, to be kept for a while and then

discarded. There are many of them in Petersburg, of these foolish young ones:

today attired in satin and velvet, but tomorrow, verily I say, sweeping the

streets with the riffraff of the alehouse. Sometimes, when you think that Dunia

may be perishing right there with them, you cannot help sinning in your heart

and wishing her in the grave..."

Such was the story of

my friend, the old stationmaster, a story often interrupted by tears, which he

wiped away with the skirt of his coat in a graphic gesture, like the zealous

Terentich in Dmitriev's beautiful ballad. These tears were partly induced by

the five glasses of rum punch that he had swilled down while he told his story;

but for all that they deeply moved my heart. After I parted with him, I could

not forget the old stationmaster, nor could I stop thinking about poor Dunia

for a long time...

Just recently, passing

through the small town of R., I remembered my old friend; I was told, however,

that the station he had ruled over had been abolished. To my question, "Is

the old stationmaster still alive?" nobody could give a satisfactory

answer. I decided to visit the place I had known so long, hired private horses,

and set out for the village of P.

This took place in the

fall. Grayish clouds covered the sky; a cold wind blew from the reaped fields,

stripping the roadside trees of their red and yellow leaves. I arrived in the

village at sundown and stopped before the building of the former station. A fat

woman came out on the porch Where poor Dunia had at one time kissed me) and

explained in response to my questions that the old stationmaster had died about

a year before, that a brewer had settled in his house, and that she was the

brewer's wife. I began to regret the useless journey and the seven rubles I had

spent in vain.

"What did he die

of?" I asked the brewer's wife.

"A glass or two

too many, Your Honor," answered she.

"And where is he

buried?"

"Yonder past the

village, next to his late wife."

"Could somebody

lead me to his grave? "

"That'd be easy

enough. Hey, Vanka! Leave that cat alone and take the gentleman to the

graveyard, show him where the stationmaster's buried."

At these words a

red-haired, one-eyed little boy in tatters ran up and led me straight to the

edge of the village.

"Did you know the

late station master I asked him on the way.

"Aye, sir, I did.

He taught me how to whittle flutes, he did. Sometimes (Lord bless him in his

grave! I he'd be coming from the pothouse and we'd be after him, 'Grandpa,

grandpa, give us nuts!' and he'd just scatter nuts among us. He used to always

play with us."

"And do any of

the travelers mention him?"

"There's few

travelers nowadays; the assessor'll turn up sometimes, but his mind is nowise

on the dead. There was a lady, though, traveled through these parts in the

summer: she did ask after the old station master and went a-visiting his

grave."

"What sort of a

lady?" I asked with curiosity.

"A wonderful

lady," replied the urchin; "she was traveling in a coach-and-six with

three little masters, a nurse, and a black pug; when they told her the old

stationmaster'd died, she started weeping and said to the children, 'You behave

yourselves while I go to the graveyard.' I offered to take her, I did, but the

lady said, 'I know the way myself.' And she gave me a silver five-kopeck

piece--such a nice lady! "

We arrived at the

graveyard, a bare place, exposed to the winds, strewn with wooden crosses,

without a single sapling to shade it. I had never seen such a mournful

cemetery.

"Here's the old

stationmaster's grave," said the boy to me, jumping on a mound of sand

with a black cross bearing a brass icon.

"And the lady

came here, did she?" I asked.

"Aye, she

did," replied Vanka; "I watched her from afar. She threw herself on

the grave and lay there for a long time. Then the lady came back to the

village, sent for the priest, gave him some money, and went on her way, and to

me she gave a silver five-kopeck piece--a wonderful lady!"

I too gave five

kopecks to the urchin, and no longer regretted either the journey or the seven

rubles spent on it.

Comments

Post a Comment