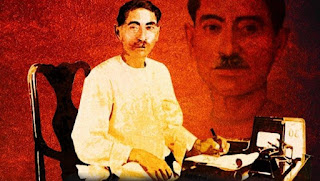

प्रेमचंद, उनका समय और हमारा समय : निरंतरता और परिवर्तन के द्वंद्व को लेकर कुछ बातें Premchand, His Era and Our Times: Some Thoughts on the Dialectics of Continuity and Change

प्रेमचंद, उनका समय

और हमारा समय : निरंतरता और परिवर्तन के द्वंद्व को लेकर कुछ बातें

अपने सृजनात्मक जीवन के बड़े हिस्से में गाँधीवादी आदर्शोन्मुखता के प्रभाव के बावजूद प्रेमचंद ने भारतीय गाँवों के भूमि-संबंधों और वर्ग-संबंधों तथा काश्तकारों और रय्यतों के जीवन और आकांक्षाओं के जो सटीक यथार्थ-चित्र अपनी रचनाओं में उपस्थित किए, वे अतुलनीय हैं। एक सच्चे कलाकार की तरह यथार्थ का कलात्मक पुनर्सृजन करते हुए प्रेमचंद ने अपनी विचारधारात्मक सीमाओं का उसीप्रकार अतिक्रमण किया, जिसप्रकार तोल्स्तोय और बाल्ज़ाक ने किया था। रूसी ग्रामीण समाज के अंतराविरोधों का सटीक चित्रण करने के नाते ही प्रतिक्रियावादी धार्मिक विचारधारा के बावजूद तोल्स्तोय 'रूसी क्रांति का दर्पण'(लेनिन) थे। इन्हीं अर्थों में प्रेमचंद भारत की राष्ट्रीय जनवादी क्रांति के अनन्य दर्पण थे और उनका लेखन अर्धसामंती-औपनिवेशिक भारत के सामाजिक-राजनीतिक जीवन का ज्वलंत साहित्यिक-ऐतिहासिक दस्तावेज़ था।

1907-08 से लेकर 1936 तक प्रेमचंद की वैचारिक अवस्थिति लगातार विकासमान

रही। गाँधी को वे अंत तक एक महामानव मानते रहे, लेकिन

गाँधीवादी राजनीति की सीमाओं और अंतरविरोधों के प्रति जीवन के अंतिम दशक में उनकी

दृष्टि अधिक से अधिक स्पष्ट होती जा रही थी और उन्हींके शब्दों में वे 'बोलशेविज़्म के उसूलों के

कायल' होते जा रहे थे। उनके उपन्यासों के कई पात्र

कांग्रेस में 'रायबहादुरों-खानबहादुरों' की बढ़ती

पैठ और कांग्रेसी राजनीति के अंतरविरोधों की आलोचना करते हैं और प्रेमचंद के लेखों

और संपादकीयों में भी (द्रष्टव्य,

'माधुरी' और 'हंस' के संपादकीय और लेख) हमें उनकी वैचारिक दुविधाओं, विकासमान

अवस्थितियों की झलक देखने को मिलती है। प्रेमचंद को जीवन ने यह मौका नहीं दिया कि

वे 1937-39 के दौरान प्रान्तों में कांग्रेसी शासन की बानगी देख सकें। 1936 में उनदा

देहांत हो गया। यदि चंद वर्ष वे और जीवित रहते, तो शायद उनकी वैचारिक अवस्थितियों में भारी

परिवर्तन हो सकते थे।

प्रेमचंद को मात्र 56 वर्षों की

आयु ही जीने को मिली। काश ! उन्हें कम से कम दो दशकों का और समय मिलता और वे पूरे

देश को खूनी दलदल में बदल देने वाले दंगों के बाद मिलने वाली

अधूरी-विखंडित-विरूपित आज़ादी के साक्षी हो पाते, तेभागा-तेलंगाना-पुनप्रा वायलार और नौसेना विद्रोह

और देशव्यापी मजदूर आंदोलनों का दौर देख पाते। प्रेमचंद यदि 1956 तक भी

जीवित रहते तो नवस्वाधीन देश के नए शासक --- देशी पूँजीपति वर्ग और उसकी नीतियों

की परिणतियों के स्वयं साक्षी हो जाते। हम अनुमान ही लगा सकते हैं कि तब भारतीय

साहित्य को क्या कुछ युगांतरकारी हासिल होता।

आज़ादी के बाद के 20-25 वर्षों के दौरान भारत के सत्ताधारी पूँजीपति वर्ग ने विश्व-पूँजीवादी

व्यवस्था में साम्राज्यवादियों के कनिष्ठ साझीदार की भूमिका निभाते हुए भारत में

पूँजीवाद के विकास के रास्ते पर आगे कदम आगे बढ़ाये। उसने बिस्मार्क, स्तोलिपिन और कमाल अतातुर्क की तरह ऊपर से, क्रमिक

विकास की गति से सामंती भूमि-सम्बन्धों को पूँजीवादी भूमि-सम्बन्धों में बदल डाला

और एक एकीकृत राष्ट्रीय बाज़ार का निर्माण किया। पूँजीवादी मार्ग पर जारी इसी

यात्रा का अंतिम और निर्णायक चरण नव-उदारवाद के दौर के रूप में 1990 से जारी

है।

पिछले करीब 40-50 वर्षों के दौरान होरी और उसके भाइयों जैसे अधिकांश निम्न-मध्यम

काश्तकार मालिक बनने के बाद, सामंती लगान की मार से नहीं बल्कि पूँजी और बाज़ार की मार से अपनी

जगह-ज़मीन से उजड़कर या तो शहरों के सर्वहारा-अर्धसर्वहारा बन चुके हैं या फिर खेत

मज़दूर बन चुके हैं। जो नकदी फसल पैदा करने लगे थे और अपनी ज़मीन बचाने में सफल रहे

थे, वे आज

उजरती मज़दूरों की श्रमशक्ति निचोड़कर मुनाफे की खेती कर रहे हैं। पर ऐसा ज़्यादातर

पुराने धनी और उच्च-मध्यम काश्तकार ही कर पाये हैं,होरी जैसे काश्तकारों का बड़ा हिस्सा तो तबाह होकर

गाँव या शहर के मजदूरों में शामिल हो चुका है। हिन्दी के कुछ साहित्यकार अक्सर

कहते हैं कि भारत के किसान आज भी प्रेमचंद के होरी की ही स्थिति में जी रहे हैं।

ऐसे लोग या तो प्रेमचंद कालीन गाँव और भूमि-सम्बन्धों को नहीं समझते, या आज के गाँवों के भूमि-सम्बन्धों और सामाजिक सम्बन्धों को नहीं

समझते, या फिर दोनों को ही नहीं समझते हैं। 1860 के भूमि सुधारों के बाद रूस में भूमि-सम्बन्धों का

जो रूपान्तरण हो रहा था,उसके

स्पष्ट चित्र हमें तोल्स्तोय के 'आन्ना करेनिना' और 'पुनरुत्थान' जैसे उपन्यासों में मिलते हैं। भूमि-सम्बन्धों के

पूँजीवादी रूपान्तरण के बाद की वर्गीय संरचना और शोषण के पूँजीवादी रूपों की बेजोड़

तस्वीर हमें बालजाक के 'किसान' उपन्यास में देखने को मिलती है। हिन्दी लेखकों की

विडम्बना यह है कि वे 'गाँव-गाँव' 'किसान-किसान' की रट तो

बहुत लगाते हैं लेकिन गाँव की ज़मीनी हक़ीक़त से बहुत दूर हैं। न तो उनके पास पिछले 50 वर्षों के

दौरान भारतीय गाँवों के सामाजिक-आर्थिक-सांस्कृतिक-राजनीतिक परिदृश्य में आए

बदलावों की कोई समझ है, न ही वे सामंती और पूँजीवादी भूमि-संबंधो के राजनीतिक अर्थशास्त्र की

कोई समझदारी रखते हैं। जो लेखक ग्रामीण यथार्थ का अनुभवसंगत प्रेक्षण कर भी लेते

हैं उनमें न तोल्स्तोय-बाल्ज़ाक-प्रेमचंद की प्रतिभा है और न ही भूमि-सम्बन्धों और

अधिरचना के अध्ययन की कोई वैचारिक दृष्टि, इसलिए ऐसे अनुभववादी लेखक भी आभासी यथार्थ को

भेदकर सारभूत यथार्थ तक नहीं पहुँच पाते और उनका लेखन प्रकृतवाद और अनुभववाद की

चौहद्दी में क़ैद होकर रह जाता है।

यही कारण है कि आज

प्रेमचंद की थोथी दुहाई देने वाले तो थोक भाव से मिल जाते हैं, लेकिन

प्रेमचंद की यथार्थवादी परंपरा का विस्तार हमें कहीं नहीं दीखता, या दीखता

भी है तो अत्यंत क्षीण रूप में। इतिहास निरंतरता और परिवर्तन के तत्वों के द्वंद्व

से होकर आगे बढ़ता है। इसमें कभी एक प्रधान पहलू होता है तो कभी दूसरा। हम प्रेमचंद

से 80 वर्षों

आगे के समय में जी रहे हैं। प्रेमचंद के समय से आज के समय में निरंतरता का पहलू

नहीं बल्कि परिवर्तन का पहलू प्रधान हो चुका है। प्रेमचंद की परंपरा को भी वही

लेखक विस्तार देंगे जो आज के समय की सामाजिक-आर्थिक संरचना, वर्ग-सम्बन्धों

और सामाजिक-सांस्कृतिक-राजनीतिक अधिरचना के सारभूत यथार्थ को प्रेमचंद जैसी ही

सटीकता के साथ पकड़ेंगे और उनका कलात्मक पुनर्सृजन करेंगे।

Premchand, His Era and Our Times: Some Thoughts on the Dialectics of Continuity and Change

Kavita Krishnapallavi

Premchand has over 300

stories to his credit. At least 20 of them can be counted among the world’s

best making him one of the greatest storytellers like Maupassant and Chekhov.

Stories such as Kafan, Poos Ki Raat, Idgah, Sawa Ser Genhun, Ramleela,

Gullidanda, Bade Bhaisahab can never be forgotten. Importantly, there is a

realistic picturisation of the rural life of a backward feudal society in

Premchand’s stories and this is rare even in the works of the world’s best.

During a large part of

his creative life, Premchand was influenced by Gandhian idealism. In spite of

that, he has painted quite a unique picture of the land-relations and

class-relations of the Indian villages as well as of the lives and desires of

the tenant farmers and ryots (peasants). In the act of his artistic recreation

of reality, Premchand, like a true artist, transcended his ideological

limitations the same way Tolstoy and Balzac did. Tolstoy, in spite of his

reactionary religious ideology, was the ‘Mirror of the Russian Revolution’

(Lenin) due to his accurate picturisation of the Russian rural society. In the

same sense, Premchand was the unique mirror of the national democratic

revolution of India and his writings were vivid literary and historical

documents of the socio-political life of semi-feudal and colonial India.

Premchand’s ideological

position was constantly evolving from 1907-08 to 1936. He considered Gandhi a

superhuman until the end, but his views about the limitations and

contradictions of Gandhian politics were becoming clearer by the last decade of

his life and in his own words, he was increasingly becoming ‘fond of the

Bolshevik principles’. Many characters of his novels criticize the increasing

power of the ‘Rai Bahadurs and Khan Bahadurs’ inside Congress as well as the

contradictions of the Congress politics. We can also find instances of

Premchand’s ideological dilemmas, evolving positions in his articles and

editorials (of Drashtavya, Madhuri and Hans). Life didn’t give him the chance

to see the examples of Congress rule in the states during 1937-39. He died in

1936. Had he lived a few more years, his ideological positions could have seen

big changes.

Premchand got to live

only for 56 years. If only he had got two more decades, if only he had

witnessed the incomplete-divided-deformed independence achieved after the riots

leading to a bloodshed across the country, if only he had seen the period of

Telangana-Tebhaga-Punnapra Vayalar and Navy uprisings and the countrywide

workers’ movements. Had he lived just until 1956, he would have witnessed

himself the native capitalist class - the new ruler of the newly independent

country - and the consequences of its policies. We can only imagine the kind of

epoch-making contributions he would have made to the Indian literature.

During the 20-25 years

after the independence, the ruling capitalist class of India moved ahead on the

path of capitalist development while playing the role of the junior partner of

the imperialists in the world-capitalist system. Like Bismarck, Stolypin and

Kemal Ataturk, it transformed the feudal land-relations into capitalist

land-relations from above in a gradual manner and built an integrated national

market. The final and the decisive phase of this journey on the capitalist path

has been continuing since 1990 in the form of neoliberalism.

During the last 40-50

years, the majority of the lower-middle tenant farmers (like Hori and his

brothers) who had become owners, have been uprooted from their place and land.

They have either joined the ranks of the urban proletariat/semi-proletariat or

transformed into agricultural laborers and this is not because of a pressure

from feudal rent, but because of the pressure of capital and market. Those who

had started growing cash crops and were successful in saving their lands, are

now involved in profiteering agriculture by expropriating the labor-power of

the wage laborers. But this has mainly become possible for the past rich and

upper-middle tenants. Majority of the tenants like Hori have been uprooted and

they have joined the ranks of the laborers in villages or cities. Some Hindi

litterateurs often say that farmers of India are still living in the conditions

of Hori. Such people either do not understand the village and land-relations of

Premchand era, or do not understand the land-relations and social relations of

today’s villages, or do not understand either. The transformation that the land-relations

were undergoing in Russia after the land-reforms of 1860, is very clearly

represented in Tolstoy’s novels like Anna Karenina and Resurrection. A unique

picture of the class structure after the capitalist transformation of the

land-relations and of the capitalist forms of exploitation is found in Balzac’s

novel ‘The Farmers’. Irony of the Indian writers is that though they keep

talking about ‘village’ and ‘farmer’, they are very far from the ground reality

of the village. Neither do they have any understanding of the changes that have

occurred in the social-economic-cultural-political scenario of the Indian

villages, nor do they have any knowledge of the political economy of the feudal

and capitalist land-relations. Those who do make an empirical observation of

the rural reality, they neither have the talent of Tolstoy-Balzac-Premchand,

nor do they have any ideological inclination toward the study of the

land-relations and superstructure. Therefore, such empiricist writers also

cannot penetrate the apparent reality to reach the essential reality and their

writings get confined within the boundaries of naturalism and empiricism.

This is the reason why we have a large number of people uselessly clamouring in the name of Premchand, but we do not find anywhere the enlargement of his realist tradition. If at all, it is seen in extremely minute forms. History moves forward with the dialectics of the elements of continuity and change. Sometimes one aspect is primary, and sometimes the other. We are 80 years ahead of Premchand’s time. During the time between his era and today, the aspect of change has become primary, not that of the continuity. Only those writers who are able to grasp the essential reality of today’s socio-economic structure, class-relations and social-cultural-political superstructure with the same accuracy with which Premchand did, can artistically recreate them and only such writers will enlarge Premchand’s tradition.

Comments

Post a Comment